Many Britons are confused with matters relating to current affairs during this politically perplexing juncture that I like to refer to as the Brexit Befuddlement. To try and decode Boris’ Brexit brain-teaser, it is important to first familiarise ourselves with a few of the terms we hear so frequently, that we seem to have become almost immune to them.

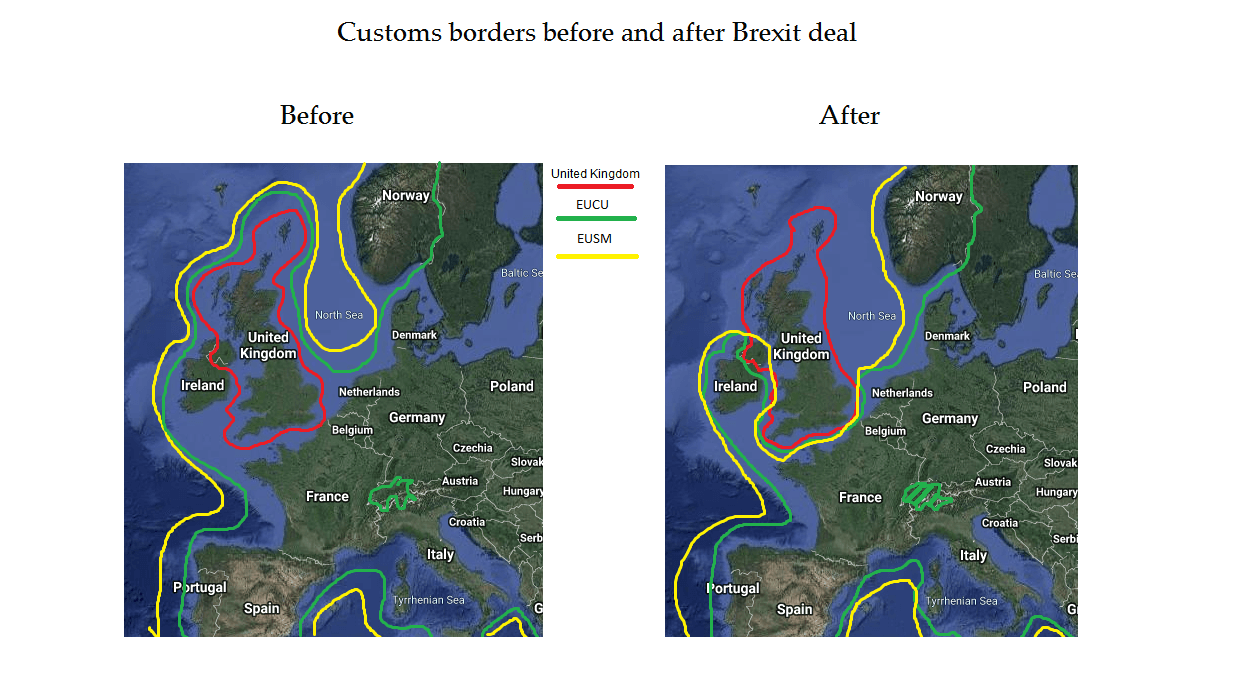

In a nutshell, Brexit is the withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union (EU), and consequently out of the European Union Customs Union (EUCU) and the European Single Market (ESM). Usually, when goods and services are imported or exported, a tax or duty is payable, known as a customs tariff. States or countries that have decided to abolish tariffs on goods and services across each other’s borders are known to have established a customs territory with the purpose of having a unified approach to customs tariffs, a customs union. These unions have common tariffs which they apply on external customs territory imports known as Common External Tariffs (CETs). The EUCU is one such example that applies CET and allows for tariff free movement of goods within its territory.

The Single Market is a form of integration that concerns the movement of goods, services, people and capital within a common framework of rules and regulations for example, in areas of animal health, manufactured goods and food safety.

The UK has been an important member state since the late 70s and European rules have become deeply imbedded in its economy which makes the task of leaving the Union not an easy one.

Once the UK decides to leave, there is a transition period ending on 31st of December 2020 during which time the UK should try to come to some sort of mutual agreement with the rest of Europe over what a future partnership might look like. It has been pointed out by one Hilary Benn MP that it is possible to extend the transition period but it would require a serving minister to propose that. Opposition members are concerned that Boris’s government may sabotage a potential deal with Europe by deliberately not seeking an extension of time. Until then, the UK would be required to follow all EU rules including the freedom of movement for EU nationals. The cost of leaving the EU (‘divorce bill’) is estimated at £33bn though some sources say it could be higher. This bill represents the UK’s share of the EU budgets and liabilities up to the end of the transition period.

The section of the Brexit withdrawal agreement that will have the most impact is that which concerns the exit of the whole of the UK from the EUCU. While this means that the UK will be able to strike trade deals with other countries without restrictions being imposed by the EU, it also means that the UK will be subject to tariffs on goods and services exported to member states of the EUCU. To counter this additional tariff expense, UK businesses will either have to make their EU customers bear the brunt by increasing sales prices to account for the tariff expense, or they will be required to reduce their original pre tariff-price to maintain the same price for the end customer after the tariff has been added. Both solutions are likely to end unfavourably for UK businesses.

The EU has forty trade deals with seventy countries to which UK has access as a member of the EU. Meanwhile, the UK has unilaterally negotiated continuity deals with fifteen countries and otherwise it will need to trade under the WTO rules. The idea of leaving Brexit is that the UK can negotiate its own trade deals though many say that the real drive for leaving the EU is to control the migration of people as most of the world is English speaking, a remnant of the British Empire. The UK exports 19% of its total to the US, 46% to the EU and 35% to the rest of the world. Therefore, the single biggest trade partner is the US and the only one where UK is a net exporter, around £41 bn. Neither the UK or Europe have a trade with the US though the UK has a mutual recognition agreement with the US. There is a real concern that a trade deal with the US will result in an increase in drug and service prices to the NHS as other competitors will be forced out. It’s vital that the NHS is unharmed and remains a publicly funded service.

The withdrawal of the UK from the customs union creates the need for a legal customs border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland as the latter is an EU country. A physical border is a sensitive issue because of the potential to reignite past religious and political tensions between Unionist and Nationalist parties. Northern Ireland will leave the customs union but to prevent the hard border, it will remain within the Single Market. This means that in practice the regulatory border for goods and services will be between Great Britain and the island of Ireland. This also means that there will need to be regulatory checks on goods moving between NI and GB but removes the need for such checks between NI and the ROI as they will effectively be part of an “an all-island regulatory zone”.

The lack of a hard border opens up the possibility of goods being transported across without being checked. The withdrawal agreement states that ordinary people will not have their baggage checked and duty will not apply to individuals, but goods that are considered “at risk” will be subject to tariffs. The nature of these “at risk” goods will be decided by a joint committee made of UK and EU representatives. All “at risk” goods moving between Great Britain and Northern Ireland are essentially crossing a regulatory border into the Single Market and will be subject to tariffs. If it can be proved that these goods have remained in Northern Ireland, the supplier will be able to claim a refund for the tariff that they have paid. If the goods have moved across the border and into Europe, the importer will not be able to claim the refund and the tariff will have been paid already.

Overall, the uncertainty of the Brexit situation has a broad set of implications for the EU and the UK in the short and long-term. With another Brexit extension looming, the future of the UK and the EU seems more uncertain than ever and we can only wait to see what the next steps will be for the United Kingdom.